Hi, Earth Rangers! My name is Claudia Haas. I’m a PhD student at Wilfrid Laurier University, and I study caribou in the Northwest Territories!

In my research, I work closely with the Łutsël K’é Dene First Nations and their Ni Hat Ni Dene Guardians. Caribou are considered one of the most important species to the Łutsël K’é Dene people. They rely on the caribou, known in their language as Ɂetthën, for physical, cultural, linguistic, emotional, and spiritual well-being.

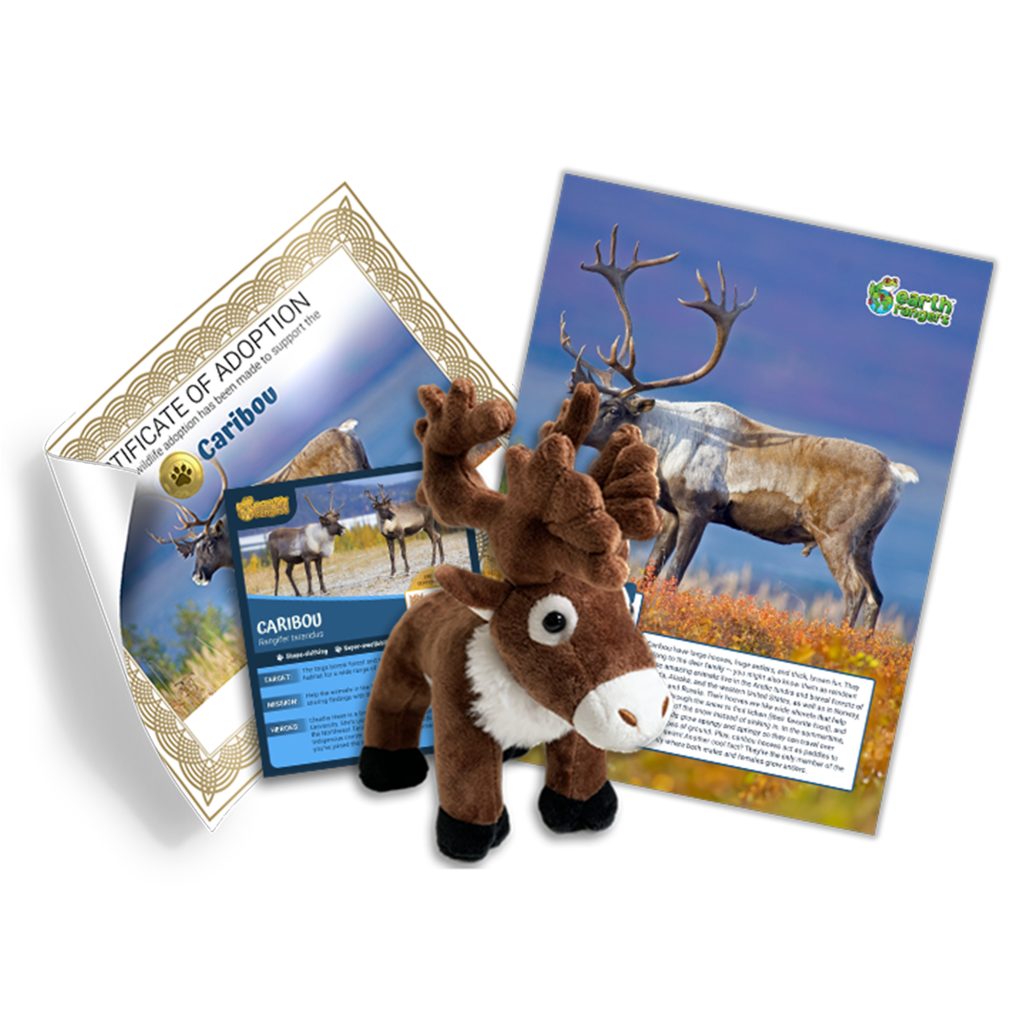

But right now, caribou are a threatened species in the Northwest Territories. When you adopt a caribou through Earth Rangers, you’re helping me work with the Łutsël K’é Dene First Nations to protect these beautiful animals.

Visit the Adoptions section of the Earth Rangers App or check out the Earth Rangers Shop to adopt your own caribou!

Protecting Caribou Habitat

In 2020, to support the recovery of caribou, Łutsël K’é released the Yúnethé Xá Ɂetthën Hádı, a community-led caribou stewardship plan.

To help with this, the community made part of their territory, Thaıdene Nëné, an Indigenous Protected Area. It’s managed by the Thaıdene Nëné Xá Dá Yáłtı: “the people that speak for Thaıdene Nëné.” This land is over 26,376 km². That’s more than four times the size of Prince Edward Island! They partner with Parks Canada and the Government of the Northwest Territories to protect the area even more, using Canadian and territorial laws.

Barren-ground caribou spend time in Thaıdene Nëné throughout the year before they travel 700 kilometres north to their breeding grounds in Nunavut. That’s like walking from Calgary to Edmonton and back!

Catching Caribou on Camera!

In 2021, I worked with Łutsël K’é to set up cameras and audio recorders at 307 sites within Thaıdene Nëné. This lets us monitor caribou and other wildlife. We took pictures and listened for wildlife for an entire year! The First Nation has since continued this project with the government, keeping some cameras and audio recorders out for longer.

Recently, I worked with Łutsël K’é to make a video describing the project for elders in the community. The video is in Dëne Sųłıné Yatı, which is the traditional language of the Łutsël K’é Dene. When Europeans came to North America, they displaced Indigenous communities like Łutsël K’é. They set up their own communities where Indigenous ones had been, and they forced many Indigenous people to move to other places. They also set up schools to teach Indigenous people European languages instead of traditional languages. This means that younger people in Łutsël K’é don’t know as much Dëne Sųłıné Yatı as older people. We added English subtitles to the video so that young people can follow along and learn words in their traditional language.

You can watch the video on YouTube!

As for my research, it takes a big team to help do all this work. We’ve looked through all the photos and listened to some of the audio. This takes a lot of time, even with help from computers.

With this data, students like me are using this information to answer important questions that will help Łutsël K’é and its partners steward Thaıdene Nëné. My labmate, Eric Jolin, discovered something interesting: For most of the year, caribou seemed to favour places with better habitat and food. But in the winter, when food is more limited, they don’t care about food and shelter as much as avoiding their biggest predator: wolves!

For myself, I’m answering questions about how caribou fit into a broader wildlife community in Thaıdene Nëné, and how this compares with wildlife communities we see in other part of the Northwest Territories. I’m talking with Indigenous communities in the Northwest Territories about their priorities and how I can answer their questions.

Want to Be a Conservationist?

If you want to be a scientist when you’re older, keep learning! Find ways to volunteer with conservation organizations in your communities. Take all the opportunities you can to learn about the plants and animals that live around you. It may feel small in the big picture of global climate change, but every little bit will help. As we learn more, we can help animals adapt, and we can protect the important connections between Canada’s Indigenous people, their land, and the animals that live there.

Great work! I would totally like to be a conservationist

Did the camera get licked.

Wow

I got my adoption kit last year. I hope all the caribou are okay

Cool!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Oh nice!!!!

I love caraboos

I love the earh rangers

Earth rangers

Nice

Hoof like a caribou