Who Hibernates?

We all know bears hibernate over winter, but who else signs up for these long sleeps? Soon there’s gonna be a bunch of animals waking up, can you guess which ones?

We all know bears hibernate over winter, but who else signs up for these long sleeps? Soon there’s gonna be a bunch of animals waking up, can you guess which ones?

At Earth Rangers, we’re gearing up for an epic event that is just around the corner: the Provincial Day of Action on Litter! It happens every year on the second Tuesday in May. This year, it’s on May 14th, and kids all across Ontario will team up to say “NO” to litter bugs, and “YES” to cleaner communities!

Ontario’s Provincial Day of Action on Litter is a special day. It’s when we’ll all come together, roll up our sleeves, and jump into the sometimes messy work of cleaning up our planet! We’ll tackle the trash that litters our streets, stopping it from ending up in parks or waterways, where it can harm animals and pollute our water. But it’s not just about cleaning! It’s also about spreading the word on why it’s important to keep our environment clean, and cheering on those who are working hard to clean up litter from nature.

At Earth Rangers, we’re all about helping the planet, protecting animals and having fun while doing it! And what better way to celebrate Ontario’s Day of Action on Litter than by completing the Shoreline Saver or Stash the Trash Mission! For a limited time only, you’ll get DOUBLE the points for completing either of these missions.

In the Stash the Trash Mission, you’ll organize your own neighbourhood cleanup to help get rid of litter!

In the Shoreline Saver in the Mission, you’ll focus your clean-up efforts near water, ensuring litter doesn’t end up creeks, rivers, lakes and even the ocean!

“I clean up because I like the animals around shorelines and I don’t want them to die.” – Earth Ranger Langley

Langley knew that cleaning up with his friends would be an adventure. So, they formed their own clean-up crew and joined the Shoreline Saver Mission. As they walked around their favourite playing area near the creek, they found lots of plastic packaging. They worked together to remove every last piece!

“It is important to you to keep your neighbourhood clean so that none of the animals go extinct and it makes a better planet”– Earth Ranger Harlow

Harlow and her brother teamed up for the Stash the Trash Mission. Setting out into their neighbourhood, they found lots paper and even a pile of egg cartons along the way. To make their clean-up more fun, they named each piece of trash’s ‘villain’ name like “Plastosaurus” or “Victoria Baggins”.

Let’s put your identification skills to the test! Can you figure out what is hidden in this picture? Make your guess in the comments.

How do whales sleep? On the sea-bed of course. But jokes aside… Marine mammals are facing a challenge: they need to breathe air regularly, so what do they do when it’s time to sleep? I’m jumping into the ocean with my brand-new SCUPA gear to find out!

Ahhhh-hhaaaaaa. Don’t you feel like yawning? I sure feel tired! But this is no time to be sleeping! There’s an underwater mystery to be solved! Today Emma throwing on her scuba gear to investigate something BIG!

Sleep is super important for everyone! A great night’s sleep helps you feel good and have nice dreams. When you get enough sleep, you stay healthy, give your mind and body a break, and feel rested. Not enough sleep can change your mood completely and even hurt your health in the long run!

When you live on land (like humans) there’s a soft ground to sleep on. You can find a comfy mattress, couch, or pile of pillows to sleep. Cats curl up, monkeys climb trees, and even birds make nests! Some animals are known for how they sleep! Bat hangs upside down, sloths are always sleepy looking… but who is the SLEEPIEST animal on Earth? Vote on the answer you think is right! If you have any thoughts, share them in the comments below.

So… what’s the answer? Be sure to listen to know the full reason why! One thing you might notice: All of these animals sleep on land. They’re safe when they lie down and rest. But what about sea creatures? Do they swallow water as they sleep? Does floating cause problems?

Some fish rest by reducing their activity, but don’t sleep like you do. Sea turtles can hold their breath for up to 7 hours, which allows them to sleep underwater for a short time if they can’t find land. What about bigger animals? Whales sleep by “turning off” part of their brains. Like humans, whales have a left and right side of their brain. To sleep, they keep one side on to work on breathing and paying attention to their environment.

Why do they do this? And why don’t we do it too then? Breathing: that is the key! Humans do what’s called “involuntary breathing” – we breathe without thinking about it. Whales are different – they do “voluntary breathing” – this means they must think to take a breath.

Sounds hard? It sure is! When diving deep down, whales are actually holding their breath! The longest whale to have held its breath was the Cuvier’s beaked whale at 222 minutes. This means they are always moving, even just a little. That is why to sleep they turn on only one part of their brain, to have the other work on breathing.

Talk about a strange biologic answer to this mystery! Do you know any other animals who sleep weirdly? What about you? Do you like sleeping on your back or sides? Or… maybe it’s a secret! I’m knackered, good night Earth Rangers!

Do you have a fun animal mystery you want us to explore?

Let us know in the comments in the Earth Rangers App!

A gift for lunch or dinner, some’bud’y is going to love this lovely rose!

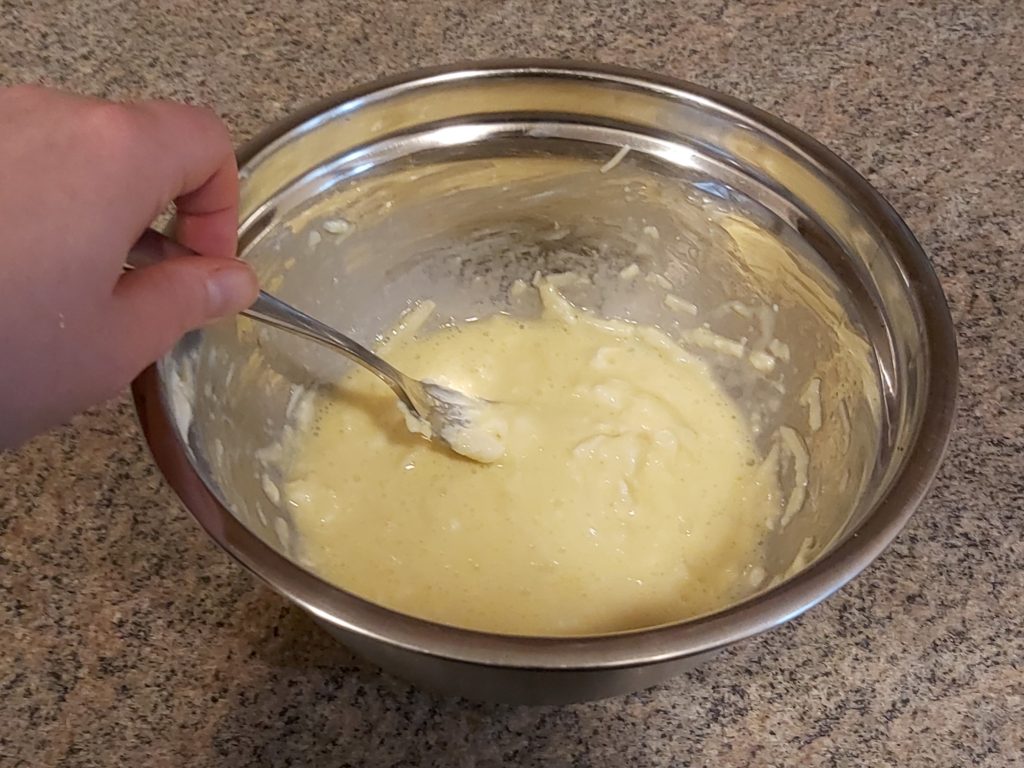

Step 1: Beat eggs, cream cheese, salt, and grated cheese in a bowl.

Step 2: Peel your carrots, zucchini and potatoes into long thin slices.

Step 3: Start by rolling oner vegetable slice into itself. Roll two or three others around it to form a cute rose!

Step 4: Pour the egg and cheese mixture into your mini tarts. Carefully place your vegetable roses in the tartlets one after the other.

Step 5: Ask an adult to help preheat the oven to 375°F. While waiting, brush some olive oil over your vegetable roses. This will prevent them from burning!

Step 6: Once ready, put your mini tarts into the oven. Let them bake for 30-40 mins.

Let your tarts cool for 10ish mins, and then they’re ready to eat!

Join us on our Carbon Footprint Investigation Mission and test your skills as a savvy shopper! Take this quiz to see if you can figure out what causes some products to have a higher carbon footprint than others!

Did you know you can lower your carbon footprint by making smarter choices when you shop? Learn more in the Carbon Footprint Investigation Mission in the Earth Rangers App!

Climate change is about more than warmer weather – it’s a big problem pushing some animals towards extinction. Let’s learn more about the different ways climate change affects animals worldwide, and find out how you can help!

With their massive claws and even bigger (and sharper!) teeth, polar bears take the cake for the fiercest-looking hunters. You might be surprised to learn, however, that their hunting style is more laidback than on the attack. These cold-weather carnivores will trek across the ice looking for holes, where they’ll wait patiently for an unknowing seal to pop its head up for air.

As temperatures in the Arctic increase and sea ice keeps disappearing, the polar bear loses the important hunting grounds it needs to survive. Without ice, it takes a lot more energy for polar bears to reach their prey, and this energy is hard to come by during the winter months when food is already limited. If climate change continues, scientists predict that over half of the polar bears in the world could disappear in the next 100 years.

If you’ve ever been quick enough to catch a frog, you know their slimy skin feels thin and delicate, but did you know this is because they breathe through their…bodies?? Frogs can absorb oxygen and release carbon dioxide through their skin, which is an important feature for these cold-blooded creatures that spend lots of time underwater and are buried in soil. Unfortunately, their thin skin also leaves them vulnerable to changes in the environment, especially changes in temperature.

Frogs will only lay eggs when the time is just right, and spring’s warm weather usually means there will be enough food around to support their growing tadpoles. But what happens if the weather gets warmer earlier in the year? If frogs lay their eggs early and the food they need isn’t available, it could cause the newly hatched tadpoles to starve.

It’s not only the direct effects of climate change that are causing problems for our frog friends. Warmer weather can cause shallow ponds to dry up, leaving the frogs that would use these ponds to lay their eggs without this important habitat.

Living in the cold Canadian north is tough, but the woodland caribou has it all figured out – and they know that lots of hair is the key to staying warm in the winter! Their bodies are covered in fur, but not just any kind of fur; the caribou’s hair is semi-hollow, which lets it trap warm air close to the caribou’s body to help insulate it and keep it warm. That’s pretty cool!

Sadly for the woodland caribou, this amazing adaptation to surviving the cold is no help in the face of climate change. Caribou spend most of their summers searching for the nutritious food they need to fill up to survive the winter, but warmer weather can melt the snow and ice that the caribou uses to get from place to place to find its food. Higher temperatures can also cause the plants that the caribou needs to survive to grow less and be less nutritious, and eating less healthy food in the summer can make it even harder for the caribou to survive the winter.

You’ve probably heard that an elephant never forgets, but did you know that sea turtles have a memory that could give them a run for their money? Even though they spend most of their lives cruising the seas, sea turtles will swim back to the same beach they hatched on to lay their eggs – even if this beach is hundreds of kilometers away!

One of the many impacts of climate change is rising sea levels. Just one higher-than-normal tide or a storm that creates big waves at sea can flood turtle nests, suffocating the eggs or washing them away completely.

Penguins are easy to spot thanks to their tuxedo-coloured coats and tiny flipper-like wings, but did you know that their characteristic colours are more functional than fashionable? Their black and white feathers might not scream camouflage to you, but they do the trick! The black backs of penguins make them hard to spot from above, and their white bellies look like the reflection of the sun on the water’s surface, helping them avoid predators while still looking like cool customers.

Unfortunately for the penguins that live in Antarctica, the melting sea ice is causing big problems, and even their camouflage can’t help. Penguins travel hundreds of kilometers across the frozen water to get to their breeding grounds, but as the ice melts this journey becomes harder and harder. If females can’t lay eggs in time, fewer new penguins are born, which can shrink colonies over the years.

You can do your part to help slow down climate change by reducing your carbon footprint when you shop. Join our team of Carbon Footprint Investigators today!

Did you know you can lower your carbon footprint by making smarter choices when you shop? Learn more in the Carbon Footprint Investigation Mission in the Earth Rangers App!

We need your help! This animal is trying to tell us something but we can’t figure it out! Do you know what these two raccoons are saying?